When writing my paper notes, I encountered the Fourier Transform and wanted to discuss it, but the topic became too long and started to overshadow the main content.

So I decided to separate this section and provide a simple introduction to the related concepts.

Trigonometric Functions

We all learned trigonometric functions when we were younger, and most of us are probably masters of trigonometry.

Trigonometric functions have widespread applications in physics and engineering, particularly in describing waves and vibrations.

A wave is essentially a way of transferring energy, and this transfer often appears in the form of "periodic oscillations."

Periodic?

A common example might be a pendulum, which swings back and forth in a periodic motion. When we observe its motion path, we can see that its displacement changes like a wave, moving from positive values to zero, then to negative values, and then repeating.

So we try to use trigonometric functions to describe the wave more precisely, mathematically represented as:

Each variable here is related to the pendulum's motion:

- : The displacement of the pendulum at time .

- : The amplitude, representing the maximum distance the pendulum swings.

- : The frequency, representing how many times the pendulum swings per second.

With the sine function, we can more accurately describe the characteristics of the wave.

If you look closely, you will notice that some waves do not start at zero but rather start oscillating after a certain time offset, which is represented by the "phase ."

The complete waveform formula can be written as:

Or it can be expressed using the cosine function:

The difference between sine and cosine waves is in the phase shift, and both can be used to describe wave variations.

Additionally, to describe the rate of change of the wave more effectively, we can use the "angular velocity ," which represents the rate of phase change per second, with the formula:

For easier observation, I have created an interactive chart where you can adjust the amplitude, frequency, and phase to observe the changes in the sine wave.

Interactive Sine Wave

Superposition of Waves

With sine and cosine waves, it's like having the basic elements of the x-axis and y-axis; we can combine different waveforms to form more complex waves, such as:

In this equation, and are coefficients that determine the size of the cosine and sine components. By superimposing multiple waves, we can form complex waveforms.

You can use the following interactive chart to adjust the parameters of two sine waves and observe the waveform formed by their superposition.

Wave Superposition

Superposition Chart

Complex Form

While the trigonometric representation of sine and cosine waves is very intuitive, using complex numbers to represent waveforms is more concise and powerful in mathematical and engineering applications.

Why?

Because complex numbers can unify the combination of sine and cosine into a single formula and make it easier to handle operations like superposition, differentiation, and integration.

Before understanding the complex form, let's quickly review the basic concept of complex numbers. A complex number consists of a real part and an imaginary part, written as:

Where:

- is the real part.

- is the imaginary part.

- is the imaginary unit, satisfying .

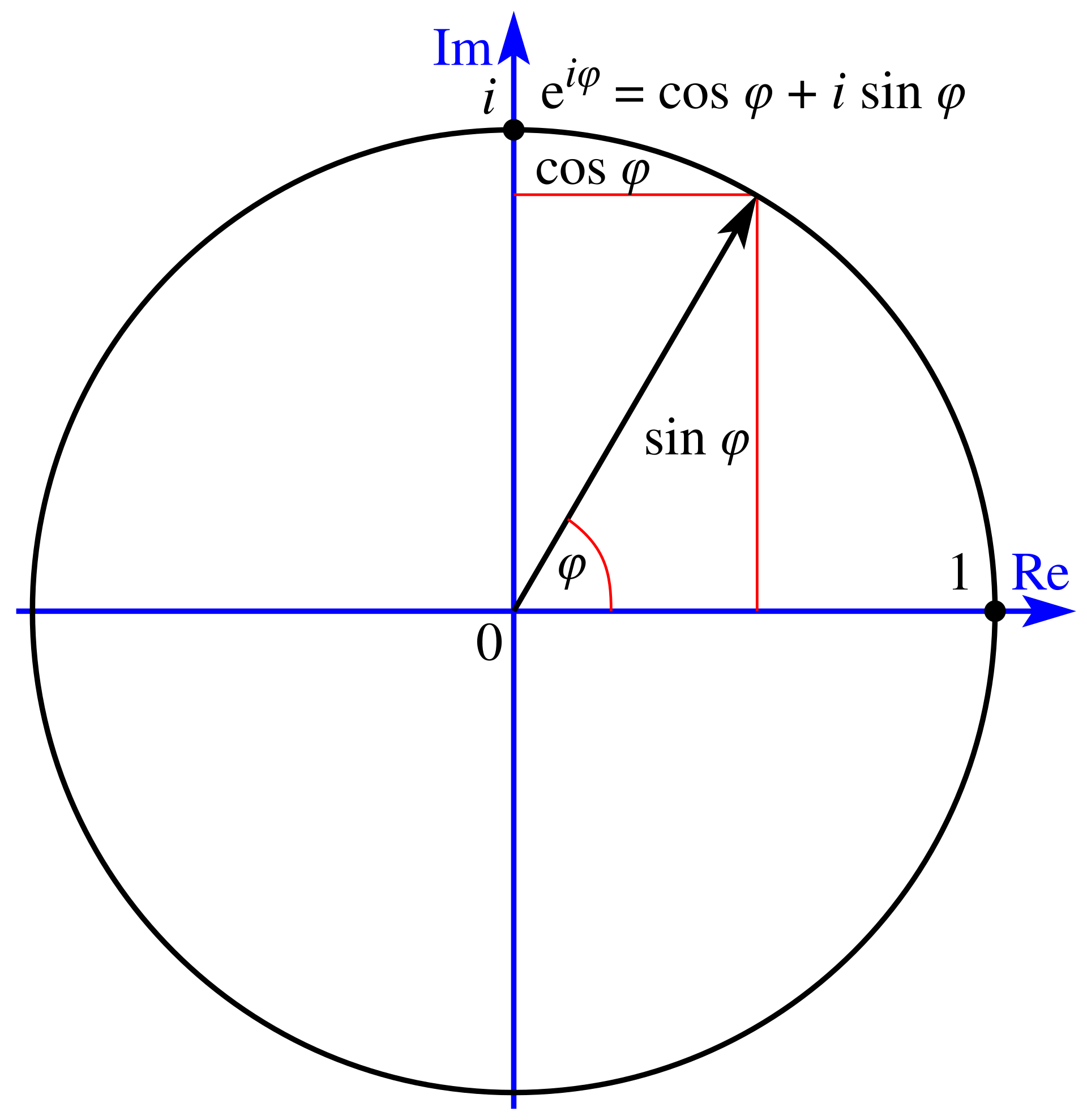

Complex numbers can also be expressed in "polar form" as:

Here:

- is the modulus of the complex number, representing the distance from the origin to the point .

- is the argument of the complex number, representing the angle of rotation from the positive real axis.

- and define the direction corresponding to the angle .

In Cartesian coordinates, the point can be converted to polar coordinates .

Substituting and into the trigonometric expression, we get .

Euler's Formula

From a mathematical perspective, the exponential function can be expanded into a power series:

This series is intuitive when is a real number, but it also applies when is a complex number.

For example, when , we substitute into the formula to get:

Expanding , and noting the periodicity of powers of (), we can separate the real and imaginary parts of the expansion:

The real part is:

This is exactly the expansion of , and similarly, the imaginary part is:

This is exactly the expansion of .

Therefore, combining the real and imaginary parts, we obtain the famous Euler's formula:

Here:

- is the exponential representation of the complex number, containing the real part and the imaginary part .

- The real and imaginary parts of the complex number correspond to the horizontal and vertical movements of the waveform.

Complex Waves

We can use Euler's formula to rewrite the waveform equation. For example, consider the following complex waveform:

Expanding and using Euler's formula, we get:

This represents the same waveform having both:

- Real part

- Imaginary part

Thus, if we want to represent sine and cosine waves using complex numbers, we can use the real and imaginary parts of the complex number to represent them:

-

Sine wave :

- We can represent it using the imaginary part of the complex number:

-

Cosine wave :

- We can represent it using the real part of the complex number:

Here, is the unified complex representation, where the real and imaginary parts correspond to the cosine and sine waves, respectively.

Superposition of Waves

If we directly use trigonometric functions to represent the superposition of two waveforms, we need to use the addition formulas for trigonometric functions, such as:

and

When superimposing two waveforms:

We would need to expand each waveform separately, apply the cosine and sine addition formulas, and then organize the real and imaginary parts.

This process can be tedious and prone to errors, especially when more waveforms are involved, as the complexity of the formulas increases exponentially.

Aside from high school students in Taiwan, I doubt anyone would want to manually calculate this, right?

In the complex form, each waveform is represented as:

The superposed waveform becomes:

The key here is that the addition of complex numbers is "linear," meaning the magnitudes and phases of the two waveforms can be directly added or kept separate without needing to expand the trigonometric formulas.

On the other hand, complex numbers inherently contain both real and imaginary parts, which already carry the information for the cosine and sine components of the waveform. Therefore, there is no need to manually handle the decomposition of trigonometric functions.

Another advantage of using complex numbers is that they allow us to clearly separate the "amplitude" and "phase" of the waveform:

- The amplitude is determined by the magnitude .

- The phase is determined by the argument .

When superimposing waveforms, these pieces of information can be handled separately or together in calculations, without needing to expand into trigonometric sum or difference formulas. For example, if we want to simply analyze the amplitude of the superposed waveform, we can directly calculate .

Finally, phase rotation of the waveform corresponds to the shift of the complex number's argument. If we need to adjust the phase of the superposed waveform, we only need to add a rotation angle to , without separately adjusting the phases of the cosine and sine components.

Fourier Transform

All that has been discussed so far serves to help us understand the mathematical formula of the Fourier Transform.

The core concept of the Fourier Transform is:

- Any signal can be represented as a sum of sine and cosine waves.

This means that even if a signal looks very complex, such as a piece of music, an image, or a pulse, we can still decompose it into simple, basic waveforms. These basic waveforms are the familiar sine and cosine waves, and they combine in different frequencies, amplitudes, and phases to form the complete signal.

Sine and cosine waves have powerful mathematical properties. For any periodic phenomenon, sine and cosine waves can be viewed as a set of "basis functions," just like the , , and coordinate axes are used to describe positions in space. By appropriately combining them, we can represent any complex shape or variation.

Suppose a signal is a time-varying function. The Fourier Transform helps us answer two key questions:

- What frequencies exist in this signal?

- What are the amplitude and phase of each frequency?

This frequency decomposition allows us to understand the signal from a completely different perspective. Instead of directly observing the waveform changing over time, we can see the signal's spectral characteristics more clearly.

The mathematical definition of the Fourier Transform provides the method for converting a signal from the "time domain" to the "frequency domain," with the core formula being:

The physical meaning of each part of the formula is as follows:

-

Original Signal :

is a function defined in the time domain. This can be any form of signal, such as the sound wave of a piece of music, the amplitude variations of an electrical signal, or a pulse sequence that jumps within a time interval.

contains the amplitude values of the signal at each moment of time .

-

Complex Exponential Function :

This is the key part of the Fourier Transform, and it is actually a combination of sine and cosine waves:

In the Fourier Transform, is used to match a complex waveform with frequency to , extracting the strength of the signal at that frequency.

The integral operation is essentially an inner product calculation, used to measure the similarity between and .

This "similarity" determines the contribution of the signal at frequency .

The Fourier Transform scans over all possible frequencies .

For each , the value calculated by the integral gives the strength at that frequency, which is why is called the "spectrum."

Instead of talking more about it, let's try calculating it ourselves:

Consider a signal with a single frequency:

Using Euler's formula, we express it as:

Now, performing the Fourier Transform:

Substituting the expression for :

Since the core of the Fourier Transform is the integral operation, its effect is to match every point in the time domain with a frequency waveform. If , the and align perfectly, and the result of the integral will be non-zero.

If , these two waveforms do not match in phase, and the integral result approaches zero.

When the frequency matches, we get:

This shows that the spectrum contains not only the strength of the frequency (given by ) but also the phase of the frequency (given by ).

This is the reason why the Fourier Transform can fully describe a signal.

Fourier Series

The Fourier Series is a special case of the Fourier Transform, mainly used for periodic signals.

Unlike the Fourier Transform, which extends the signal's spectrum to a continuous range of frequencies, the Fourier Series focuses on using a set of "discrete frequencies" to describe a periodic signal.

The core concept of the Fourier Series is:

- Any periodic signal can be represented as a linear combination of sine and cosine waves at discrete frequencies.

This means that as long as the signal is periodic, we can approximate it using a finite number of sine and cosine waves, and as the frequency combinations increase, the approximation becomes more accurate.

Suppose a periodic signal with period can be represented by the Fourier Series as:

Here, are the coefficients of the Fourier Series, representing the amplitudes of the sine and cosine waves at different frequencies, and these coefficients are determined by the following formulas:

-

DC Component ():

It represents the average value of the signal, or the DC component over one period.

-

Cosine Coefficients ():

It represents the amplitude of the cosine wave at frequency .

-

Sine Coefficients ():

It represents the amplitude of the sine wave at frequency .

Similarly, to simplify the representation and computation, the Fourier Series is often written in complex form:

Where are the complex coefficients, defined as:

In this form:

- The real part corresponds to .

- The imaginary part corresponds to .

The Fourier Series has wide applications in engineering and science, such as studying periodic vibrations in mechanical structures and analyzing periodic electrical signals, like square waves, triangle waves, and sawtooth waves.

Conclusion

Here, we can only briefly introduce the relevant concepts of the Fourier Transform.

There is more to explore, such as the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT), Fast Fourier Transform (FFT), the relationship between Fourier Transform and convolution, frequency-domain filter design and implementation, and the extensions of Fourier analysis in quantum physics and image processing, which could take days to fully discuss.

Interested readers can consult further resources to learn more about the principles and applications of Fourier Transform.

With the remaining space, I'll add a fun interactive activity at the end to experience the charm of Fourier!

Interactive Activity

Based on the settings, the program will plot the corresponding waveform in the time domain and show its analysis results in the frequency domain.

You will see that the frequency domain distribution matches the values on the "settings panel," with other frequencies generated to approximate the waveform.

Time Domain Signal

Frequency Domain Signal

☕ Fuel my writing with a coffee

Your support keeps my AI & full-stack guides coming.

AI / Full-Stack / Custom — All In

From idea to launch—efficient systems that are future-ready.

All-In Bundle

- Consulting + Dev + Deploy

- Maintenance & upgrades

🚀 Ready for your next project?

Need a tech partner or custom solution? Let's connect.