[20.05] SEED

The Seed of Language

SEED: Semantics Enhanced Encoder-Decoder Framework for Scene Text Recognition

It seems that models relying solely on visual features have hit a performance plateau.

So, is there a way to incorporate more linguistic information into the process?

Problem Definition

Inspired by advancements in NLP, many Scene Text Recognition (STR) studies have begun to adopt attention mechanisms to tackle challenges.

For regular text, encoder-decoder architectures typically use convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) with attention mechanisms to predict characters step by step. For irregular text, multi-directional encoding and 2D attention methods are applied.

So...

Since STR models already borrow from NLP frameworks, why not take it a step further?

The "language" aspect in language models is actually a valuable clue.

In this paper, the authors introduce additional "semantic information" as a global reference to assist in the decoding process, marking one of the earliest explorations of multimodal feasibility in the STR field.

Solution

Model Architecture

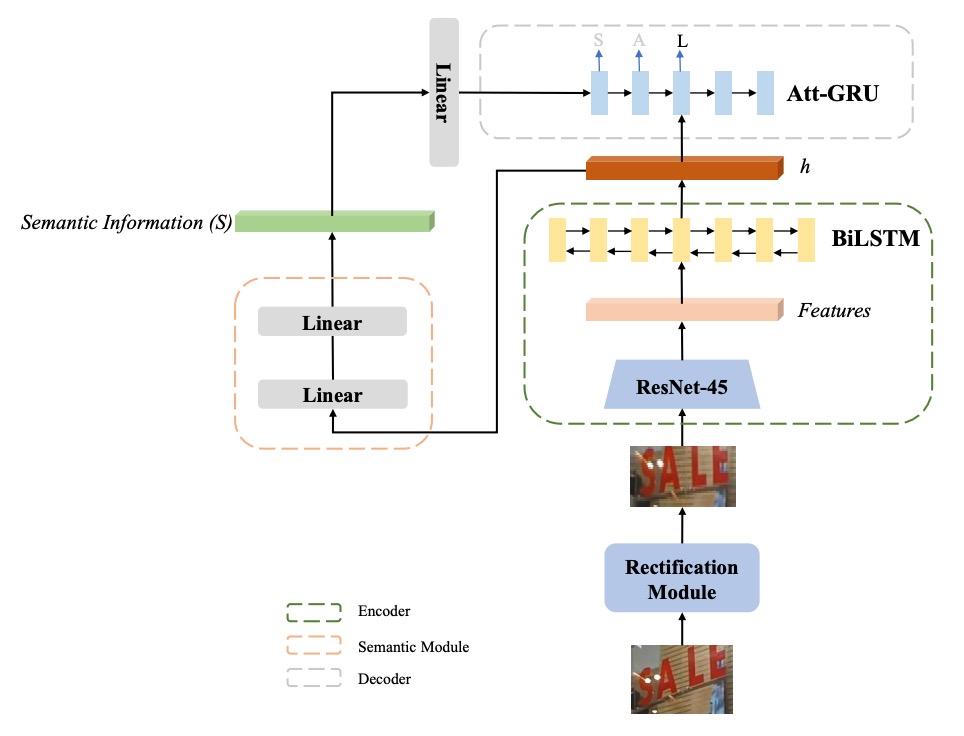

Building on ASTER, the authors propose the "Semantics-Enhanced ASTER (SE-ASTER)" method, as illustrated above.

SE-ASTER consists of four main modules:

- Rectification Module: For correcting irregular text images;

- Encoder: For extracting rich visual features;

- Semantic Module: For predicting semantic information from visual features;

- Decoder: For producing the final recognition result.

Initially, the input image passes through the Rectification Module, where shallow CNN layers predict control points, and the image is rectified using Thin-plate Splines (TPS).

For more on TPS rectification, refer to our previous article:

The rectified image is then fed into the Encoder, which generates visual features. The Encoder comprises a 45-layer ResNet CNN and a BiLSTM with 256 hidden units, producing a feature sequence with dimensions , where represents the width of the last CNN feature map and is the feature dimension.

The output feature sequence serves two purposes:

- Provides input for the Semantic Module to predict semantic information;

- Serves as input to the Decoder.

To predict semantic information, the feature sequence is flattened into a 1-dimensional feature vector with dimension .

Semantic information is then calculated using two linear functions:

where are trainable weights, and is the ReLU activation function. The semantic information is supervised with pre-trained word embeddings from a FastText model.

The authors experimented with using the final hidden state of the BiLSTM in the encoder for semantic information prediction, but it yielded subpar results. They theorize that a broader feature context is needed for semantic prediction, making the encoder's output more suitable.

Pre-trained Language Model

For the language model, the authors chose FastText as the pre-trained language model (based on the skip-gram method).

Assume that represents a sentence in the corpus, where is the sentence length. In the skip-gram model, a word is represented by an embedding vector and is input to a simple feed-forward neural network with the objective of predicting the context:

During training, the embedding vector is optimized such that each word's final embedding vector closely matches that of semantically similar words. FastText further embeds subwords and uses them to form the final embedding of word .

For example, if , , and the word is "where," the set of subwords would be . The word's representation is the combination of subword embedding vectors and its embedding vector.

Thus, FastText addresses the "Out of Vocabulary" (OOV) problem.

Why not use RoBERTa or BERT instead in 2020?

After supervising the visual features with the language model, the semantic-enhanced features are used as initialization input to the Decoder, which is crucial; ablation studies show that excluding semantic information from the decoder yields no significant performance boost.

Loss Function

During training, the authors apply supervision signals to both the Semantic Module and Decoder, enabling SE-ASTER to train end-to-end.

The loss function is defined as:

where is the standard cross-entropy loss, measuring the difference between the predicted probabilities and the ground truth labels.

is the cosine embedding loss for semantic information:

where is the predicted semantic information, and is the embedding of the transcription label from the pre-trained FastText model, aiming to maximize similarity between predicted semantic information and the FastText embeddings of the target words.

is a balancing hyperparameter, set to 1.

The authors chose a simple cosine loss instead of contrastive loss here to speed up training.

Implementation Details

The pre-trained FastText model used is the official version, trained on Common Crawl and Wikipedia datasets. It recognizes 97 symbols, including numbers, uppercase and lowercase letters, 32 punctuation marks, end-of-sequence, padding, and unknown symbols.

Input images are resized to 64 × 256 without preserving the aspect ratio. The ADADELTA algorithm optimizes the objective function.

Without pre-training or data augmentation, the model is trained on SynthText and Synth90K datasets for 6 epochs with a batch size of 512. The initial learning rate is set to 1.0, decaying to 0.1 in the 4th epoch and 0.01 in the 5th epoch. Training is conducted on an NVIDIA M40 GPU.

For inference, image sizes match those in training. Beam search is applied in GRU decoding, retaining the top ( k = 5 ) candidates by cumulative score in all experiments.

Discussion

Comparison with Recent Methods

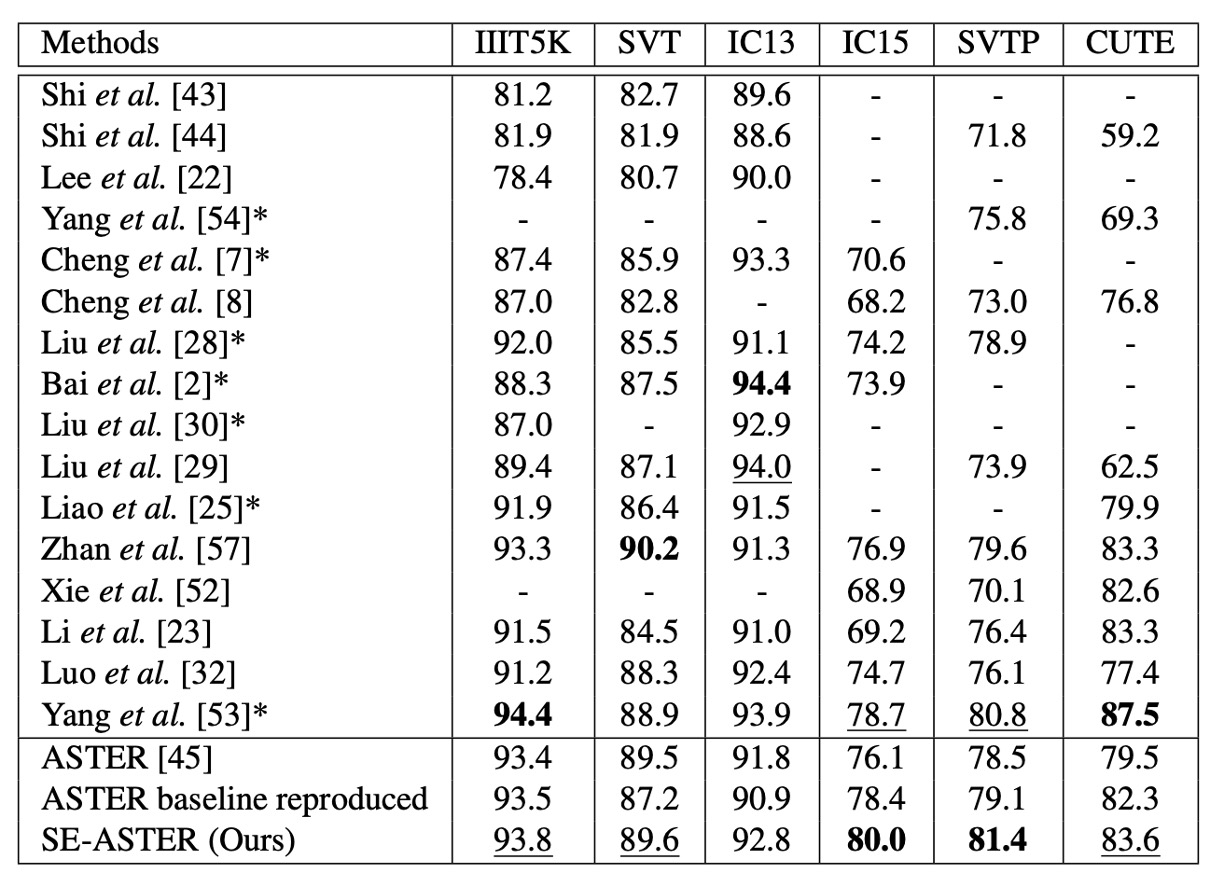

The authors compared their proposed method with previous state-of-the-art techniques across several benchmark datasets, as shown in the table above.

Without using lexicons and with only word-level annotations, SE-ASTER achieved the top result on 2 of the 6 benchmark datasets and the second-best result on 3 others. Notably, the proposed method demonstrated excellent performance on low-quality datasets, such as IC15 and SVTP.

SE-ASTER improved performance on IC15 by 3.9% (from 76.1% to 80.0%) and on SVTP by 2.9% (from 78.5% to 81.4%), showing significant gains over ASTER. Additionally, despite using a less powerful backbone network and no character-level annotations, SE-ASTER outperformed the state-of-the-art ScRN on SVTP and IC15 by 0.6% and 1.3%, respectively.

Visualization of Results

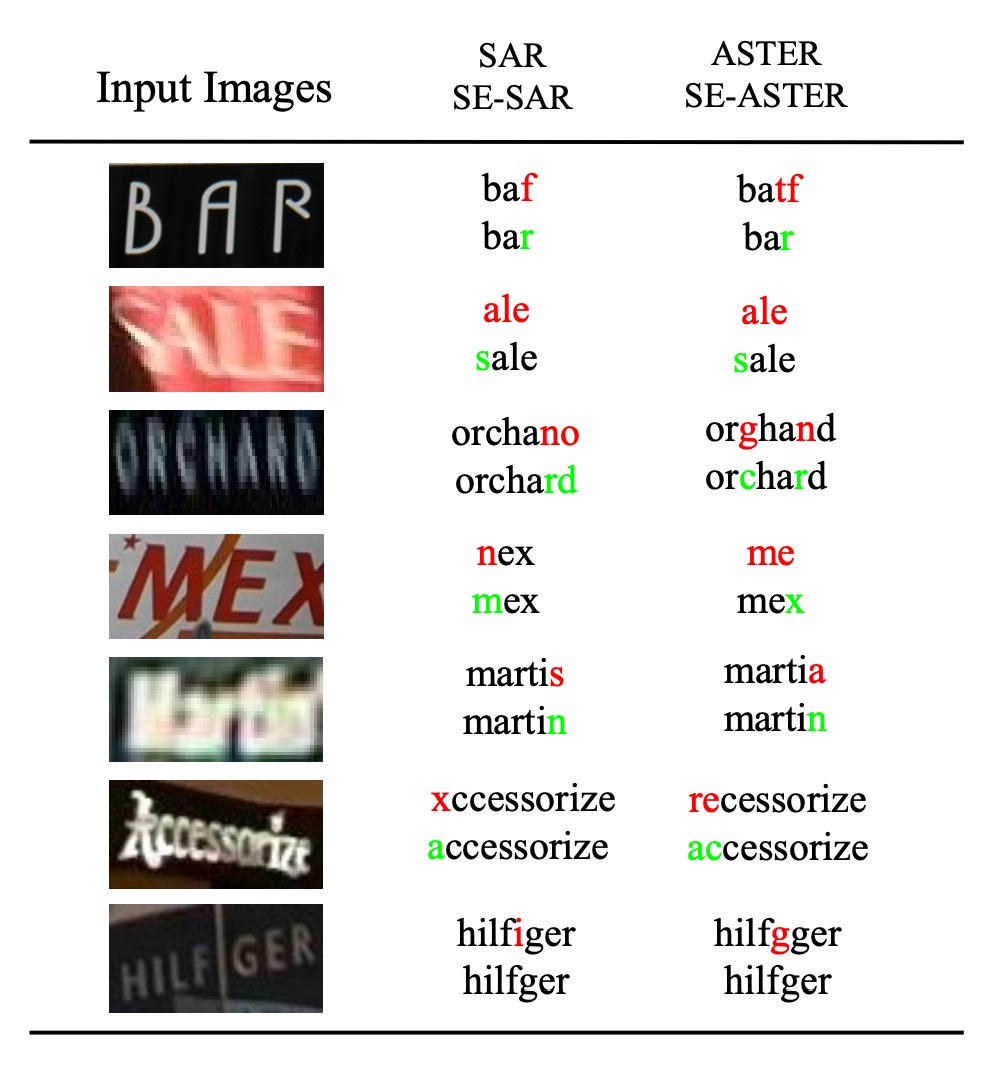

The authors visualized results on some low-quality images, including examples with blurring or occlusion, as shown in the figure above.

These results illustrate SE-ASTER’s robustness in handling low-quality images. The authors attribute this to the semantic information, which provides the decoder with effective global features, enhancing the model's resilience to interference within the image.

In the above figure, SE-SAR applies the same semantic-enhanced architecture to the SAR framework, demonstrating similar advantages of incorporating language models. For more on SAR, refer to our previous article:

Conclusion

The integration of language models introduces a fresh perspective to the STR field, with SE-ASTER achieving strong performance across multiple benchmark datasets and exhibiting robustness on low-quality images.

As language models gain traction in STR research, their use is becoming a prominent trend. Although potential side effects may arise from using language models, they present an emerging and worthwhile direction for further exploration.