[21.03] CLIP

Breaking the Dimensional Barrier

Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision

Try Describing This Image:

- A cup of coffee... um, with a book underneath the cup? Both are on a table?

- Is this a corner of a café in the morning?

- Brown table, brown chairs, and brown coffee? (Come on, be serious!)

- …

In fact, this image was generated from the following description:

On a peaceful morning, sunlight softly filters through the gaps in the curtains, gently illuminating a simple wooden table. On the table rests a freshly brewed cup of coffee, and the aroma of the coffee mingles with the sunlight, evoking warmth and hope for the day ahead. The shadow of the cup stretches across the table, casting a long reflection, which, along with the green plants by the window, creates a beautiful scene. The surface of the coffee ripples slightly, as if whispering the calmness of the morning and the beauty of life. Beside the cup, an open book lies quietly, waiting to be read. This tranquil morning scene, with coffee, sunlight, greenery, and books, forms a warm and serene moment, telling a story of life’s simplicity and beauty.

When trying to describe this image, you might realize that existing datasets, like ImageNet, with their 20,000 categories and millions of images, feel inadequate.

- There are countless ways to describe the same image.

Defining the Problem

In contrast to the single hierarchical labels in ImageNet, humans can interpret an image from countless angles—through color, shape, emotions, and narrative context.

This highlights the distinction between unimodal learning and multimodal learning: the former processes information from a single perspective, while the latter integrates different types of information, providing a richer and more comprehensive interpretation.

Traditional datasets like ImageNet often ignore meaningful information, such as object relationships, context, or emotions evoked by an image.

The goal of CLIP is to break these limitations by integrating information from different sources, like text and images, to enhance the model’s interpretive capacity—bringing it closer to human-level perception and understanding.

So, how did they achieve this?

The Solution

Model Architecture

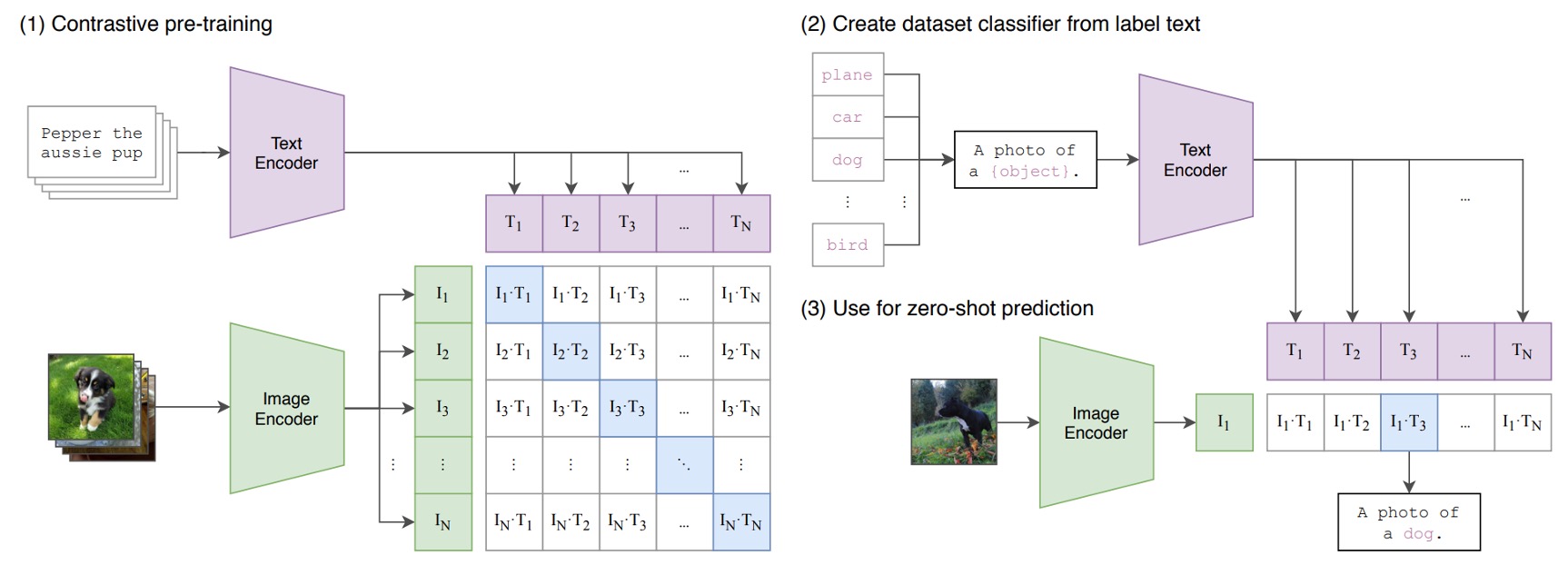

The above diagram illustrates the pre-training architecture of CLIP.

Consider a pair of image and text—such as a picture of a dog with the caption, “a cute puppy.”

In a training batch, CLIP receives multiple such pairs. The image encoder processes the images (via ResNet or ViT) to extract features, while the text encoder (using a Transformer) extracts textual features.

The model compares these features to ensure that the cosine similarity between correctly paired image-text (like the dog image and the caption “a cute puppy”) is maximized, while the similarity between mismatched pairs (like a dog image and the caption “an apple”) is minimized.

What next?

Next, they fed 400 million image-text pairs into the model for training!

Large-Scale Dataset

Initially, the authors used datasets like MS-COCO, Visual Genome, and YFCC100M.

However, these datasets were too small for modern needs. MS-COCO and Visual Genome only offer around 100,000 training images—insufficient compared to other computer vision systems processing billions of Instagram photos. YFCC100M, though larger with 100 million images, suffers from poor metadata quality (e.g., camera exposure settings as captions).

The solution? Build a new large-scale dataset—WIT (WebImageText)—comprising 400 million image-text pairs collected from public web sources.

Here is the dataset download link: WIT: Wikipedia-based Image Text Dataset

Training Details

The authors trained a series of 5 ResNet and 3 Vision Transformer (ViT) models.

- ResNet Series: They trained ResNet-50 and ResNet-101, followed by scaled versions like RN50x4, RN50x16, and RN50x64—each representing 4x, 16x, and 64x the computational power of ResNet-50.

- ViT Models: The team trained ViT-B/32, ViT-B/16, and ViT-L/14, running each for 32 epochs using the Adam optimizer with weight decay regularization and cosine learning rate scheduling.

Training the largest ResNet model (RN50x64) required 592 V100 GPUs for 18 days, while ViT-L/14 needed 256 V100 GPUs for 12 days. The ViT-L/14 model received additional fine-tuning at 336-pixel resolution, designated as ViT-L/14@336px.

592 V100 GPUs? Simply incredible!

Discussion

Zero-Shot Learning

CLIP excels in some areas but has room for improvement:

-

Performance on Specific Datasets: In datasets with clear feature expressions, CLIP’s zero-shot performance rivals or surpasses fully supervised classifiers.

-

Few-Shot Matching: CLIP can identify new categories (like “zebra”) from textual descriptions, while few-shot classifiers require more training data to achieve comparable results.

-

Transferability Across Datasets: CLIP’s transferability varies across datasets. It performs well with simpler datasets but struggles with more complex ones.

-

Comparison with Supervised Classifiers: While supervised classifiers often outperform CLIP, zero-shot learning provides a powerful alternative for certain tasks.

-

Scaling Trends: The performance improvements suggest further potential for zero-shot learning by expanding data and refining model features.

Is CLIP Truly Generalizable?

CLIP outperforms traditional ImageNet-trained models across new domains but still experiences slight performance drops when dealing with unseen distributions.

Human vs. Machine

In experiments using datasets like Oxford IIT Pets, humans achieved higher accuracy (up to 94%), especially with a few reference samples. In contrast, CLIP struggled to improve with limited samples, revealing a gap in few-shot learning capabilities compared to humans.

Overlap in Data

During pre-training, overlap between the training dataset and evaluation sets raised concerns about inflated performance. While some datasets showed overlap (e.g., Country211), the impact on accuracy was minimal—indicating that overlapping data did not significantly boost performance.

Limitations

Despite its promise, CLIP faces several challenges:

-

Performance Gaps: CLIP's performance still lags behind state-of-the-art supervised models on many datasets, even with scaling.

-

Few-Shot Learning Deficiencies: CLIP struggles with fine-grained tasks, like distinguishing car models or counting objects.

-

Generalization Challenges: CLIP’s performance drops significantly on datasets like MNIST, highlighting the limitations of relying solely on diverse datasets for generalization.

-

Data and Computational Costs: Training CLIP demands extensive data and computation, limiting its accessibility.

-

Evaluation Challenges: The model relies heavily on zero-shot settings, but performance unexpectedly drops when transitioning to few-shot tasks—indicating room for optimization.

-

Bias and Ethical Issues: CLIP’s reliance on web data introduces societal biases, necessitating further research to address these concerns.

Ethical Concerns

-

Bias: CLIP's training data may reflect social biases, potentially amplifying discrimination or inequality in applications.

-

Surveillance: CLIP’s capabilities raise privacy concerns when used in surveillance tasks, especially for facial recognition or behavior analysis.

Conclusion

CLIP demonstrates how large-scale pre-training from natural language supervision can revolutionize computer vision, achieving impressive performance in zero-shot learning and task transfer.

Key Contributions:

-

Multimodal Learning: CLIP’s ability to integrate images and text offers unprecedented versatility.

-

Zero-Shot Learning: By leveraging natural language, CLIP performs well even without task-specific training data.

-

Scalability: With sufficient data, CLIP approaches the performance of supervised models.

Future Directions:

-

Improved Interpretability: While CLIP provides high-level explanations, it lacks detailed interpretability and transparency.

-

Enhanced Few-Shot Learning: Integrating few-shot methods could further improve performance.

CLIP opens new avenues for multimodal learning, but it also presents challenges—highlighting the importance of balancing performance with ethical considerations for future development.