[21.03] DBB

Six Disciples

Diverse Branch Block: Building a Convolution as an Inception-like Unit

After reading this paper, I never found the time to organize my thoughts.

Now, let's discuss the content of this paper.

Problem Definition

Do you remember RepVGG?

To briefly recap, "re-parameterization" refers to using more complex structures or multiple branches during training to learn diverse feature representations. After the model is trained, these complex structures' parameters are integrated and merged into a simplified model, so that during inference, it retains the efficiency of a "single-path convolution."

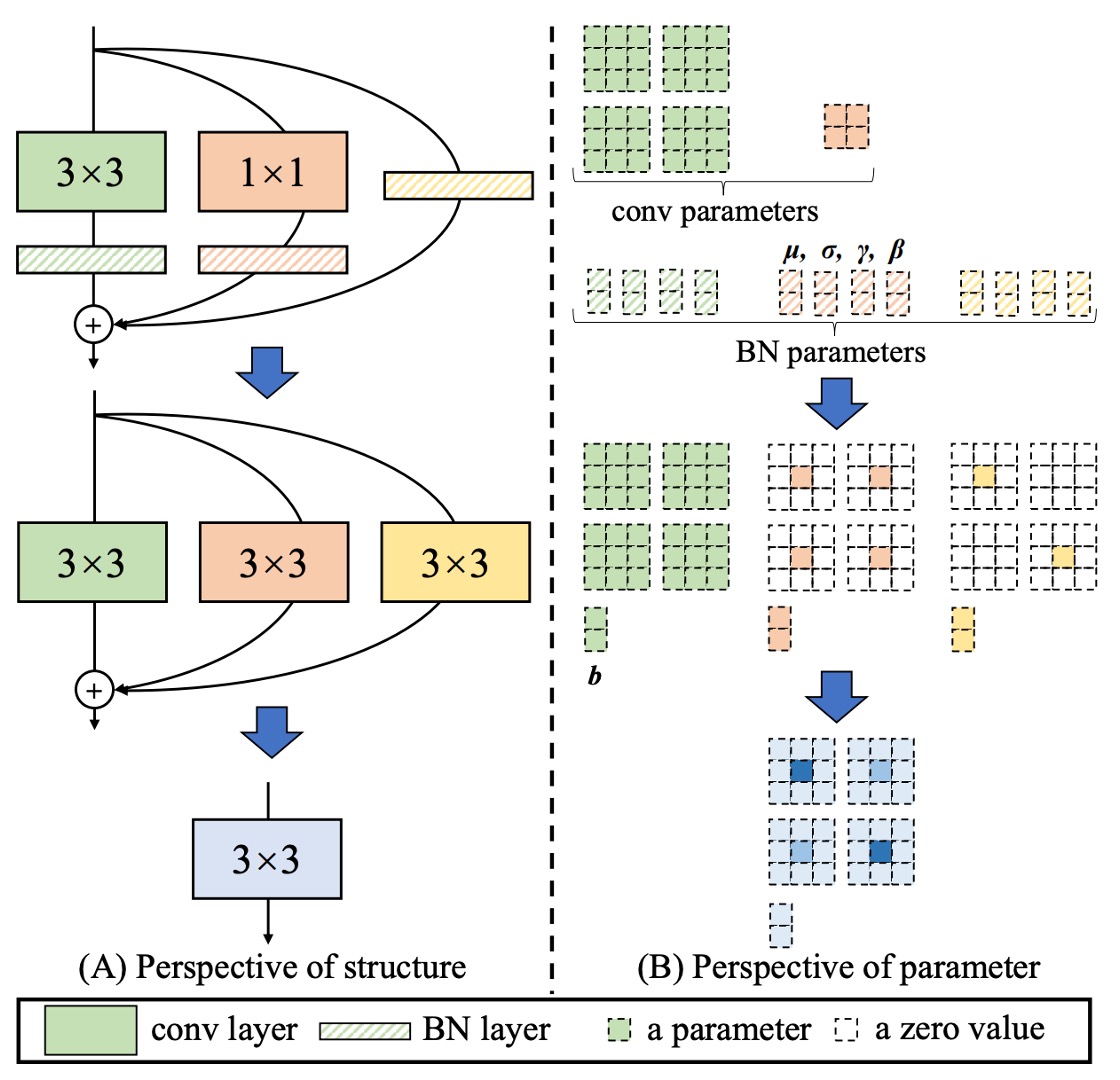

RepVGG is a representative of this concept, as shown in the diagram below:

During training, additional 1×1 convolutions, identity branches, etc., are introduced. Finally, they are all "condensed" into pure 3×3 convolution layers, making the inference structure as lightweight and efficient as the classic VGG.

If you're unfamiliar with the concept of re-parameterization, we recommend you first read the RepVGG paper:

After reading RepVGG, you might wonder whether this branch design could be even more diverse.

The authors of this paper thought the same way, perhaps we can find a more diverse design that allows the model to learn more varied features during training:

- As long as we can consolidate them into a single branch during inference, it's worth considering!

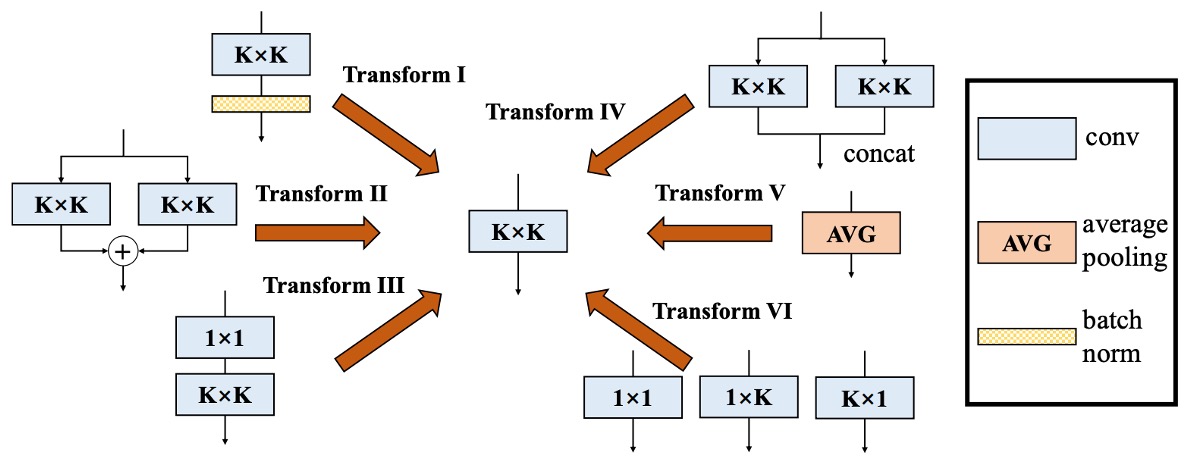

Based on this goal, the authors ultimately proposed "six" solutions.

Solution

Type One: Conv-BN

Common convolution layers are often followed by a Batch Normalization (BN) layer, i.e., "conv → BN."

During inference, BN can be viewed as "performing a linear transformation on the same output channel": subtracting the channel mean , dividing by the standard deviation , multiplying by the learned coefficient , and adding the bias .

We can merge BN with the preceding convolution into a new convolution kernel and bias using "homogeneity and additivity," as follows:

This way, there's no need to explicitly separate "convolution + BN" during inference, but instead directly use the new convolution kernel and new bias .

Type Two: Branch Add

Branch addition refers to adding the outputs of two convolutions with the same configuration (e.g., same kernel size, same number of channels).

From additivity, after applying "Type One" to both convolutions, if their kernels are and biases are , the merged result is:

Therefore, as long as the branches are parallel and spatially aligned, they can be summed into the same convolution kernel.

Type Three: Sequential Conv

For sequential convolution layers, such as "1 × 1 conv → BN → K × K conv → BN," they can also be merged into an equivalent K × K convolution. The merging process is as follows:

- First, merge the 1 × 1 conv + BN into an equivalent 1 × 1 convolution (obtaining ).

- Then, merge the K × K conv + BN into another equivalent K × K convolution (obtaining ).

- Finally, combine these two layers.

Since the 1 × 1 conv does not change the spatial dimension but alters the linear combination of channels, we can use the concept of "transpose" to merge them into the K × K convolution kernel. Also, the bias from the previous layer will "accumulate" as a constant when passing through the next convolution.

After organizing, we get a new K × K convolution , completing the merging of sequential layers.

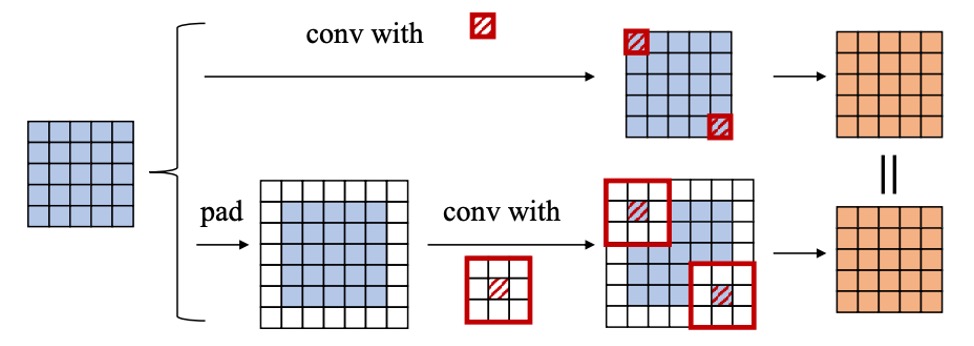

Padding Issue

If zero padding is applied in both layers, theoretically, an extra ring of zeros would be added to the spatial dimension, causing the outputs from the previous layer to misalign with the sliding window of the next layer. The authors propose two solutions:

- Only pad the first convolution, and not the second.

- Pad using "" to maintain consistency.

This part involves detailed implementation concerns, but the principle is to ensure spatial alignment.

Type Four: Depth Concat

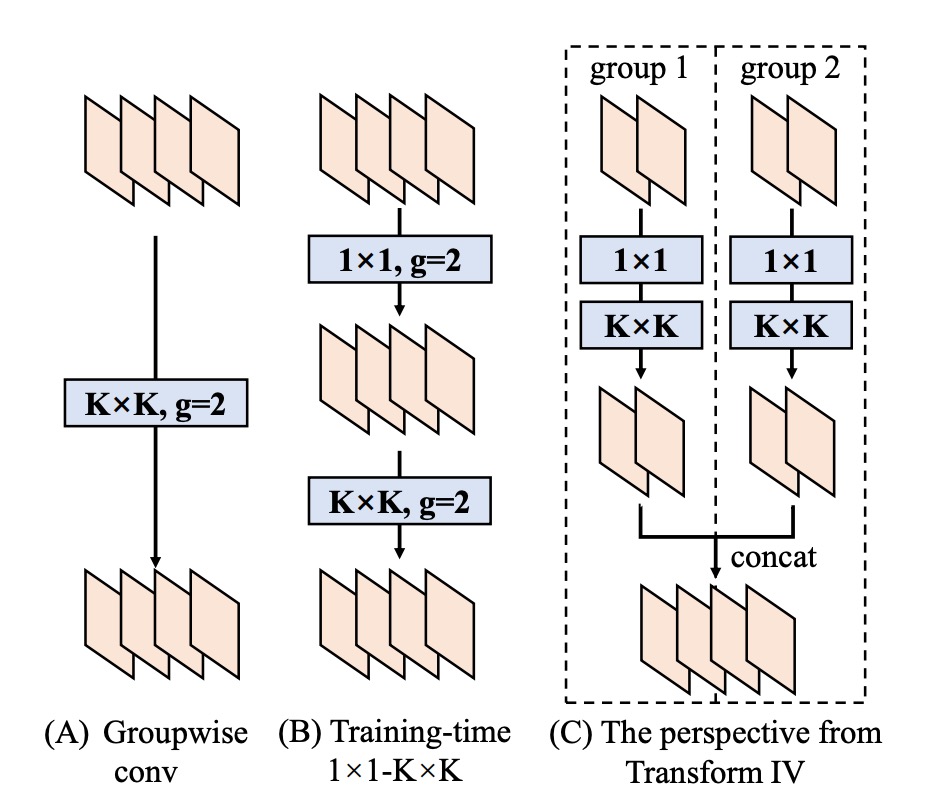

Inception-like structures often use "depth concatenation" to combine the outputs of multiple branches along the channel dimension.

If these branches are simply "convolutions" and spatially aligned, we can directly concatenate their convolution kernels along the output dimension:

This is equivalent to merging all the original output channels into a single large convolution. A similar approach can be applied to grouped convolutions, where channel-wise splitting and merging are performed.

Type Five: Average Pooling

Average pooling can actually be considered a special type of convolution.

If we have a pooling kernel of size , it is equivalent to a convolution with a kernel of the same size, where the center is a constant and other positions are 0:

When the stride is 1, it simply smooths the input. If the stride > 1, it results in downsampling.

Therefore, if average pooling is used in a branch, it can be directly converted into a fixed-parameter convolution kernel and then combined with other branches using the previously discussed transformations (such as additivity).

Type Six: Multi-scale Conv

If the network contains convolution kernels of different sizes (e.g., , , , , etc.), they can all be viewed as cases where certain positions in a convolution kernel are "zero-padded."

In this way, all different sizes (as long as they are not larger than ) can be "expanded" to the same convolution kernel dimension, keeping them aligned, and ultimately merged additively.

Experimental Setup

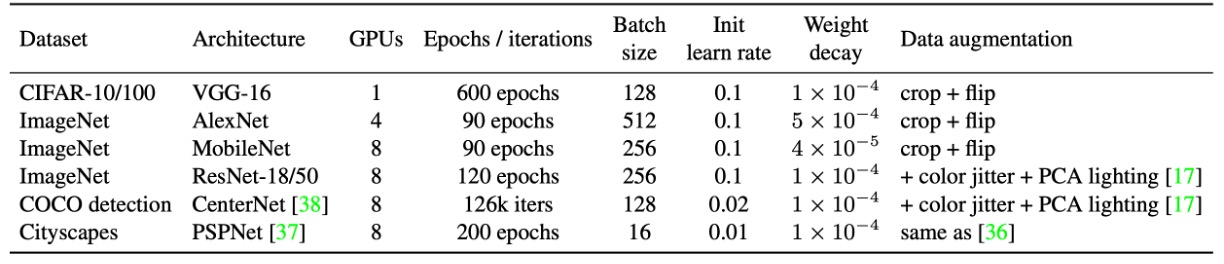

The table above summarizes the experimental configuration.

The authors used standard data augmentation on CIFAR-10/100, including expanding images to 40×40, random cropping, and horizontal flipping. For quick feasibility verification, VGG-16 was chosen, and following the ACNet approach, the original two FC layers were replaced with global average pooling, followed by a single fully connected layer with 512 neurons. For fair comparison, BN was added to each convolution layer of VGG.

ImageNet-1K contains 1.28 million training images and 50,000 validation images. Small models (AlexNet, MobileNet) used standard augmentation (random cropping and flipping), while ResNet-18/50 also included color jitter and lighting variations. AlexNet was designed similarly to ACNet, without local response normalization (LRN), and BN was added after each convolution. The learning rate for both CIFAR and ImageNet was adjusted using cosine annealing (initial value 0.1).

For COCO detection, CenterNet was used, trained for 126k iterations with an initial learning rate of 0.02, decaying by 0.1 at 81k and 108k iterations. Cityscapes semantic segmentation followed the official PSPNet settings, using a poly learning rate strategy (base 0.01, exponent 0.9), for a total of 200 epochs.

In all architectures, the authors replaced K×K convolutions (1 < K < 7) and subsequent BN layers with DBB, forming DBB-Net. Larger convolutions (e.g., 7×7, 11×11) were not included in the experiment, as they are less frequently used in model design. All models were trained under the same configuration, and DBB-Net was eventually converted back to the original structure for testing. All experiments were conducted in PyTorch.

Discussion

Comparison with Other Methods

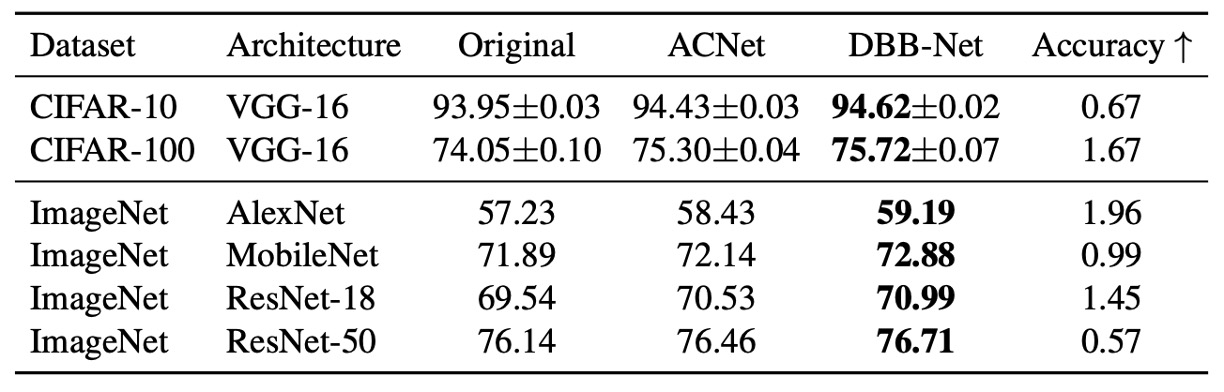

The experimental results, as shown in the table above, demonstrate significant and consistent performance improvements with DBB-Net on both CIFAR and ImageNet:

- VGG-16 improved by 0.67% on CIFAR-10 and 1.67% on CIFAR-100,

- AlexNet improved by 1.96% on ImageNet,

- MobileNet improved by 0.99%,

- ResNet-18/50 improved by 1.45%/0.57%.

ACNet, which theoretically is a special case of DBB, performed worse than DBB in the experiments, indicating that merging paths of varying complexity, similar to Inception, is more beneficial than relying solely on multi-scale convolution feature aggregation.

Ablation Study

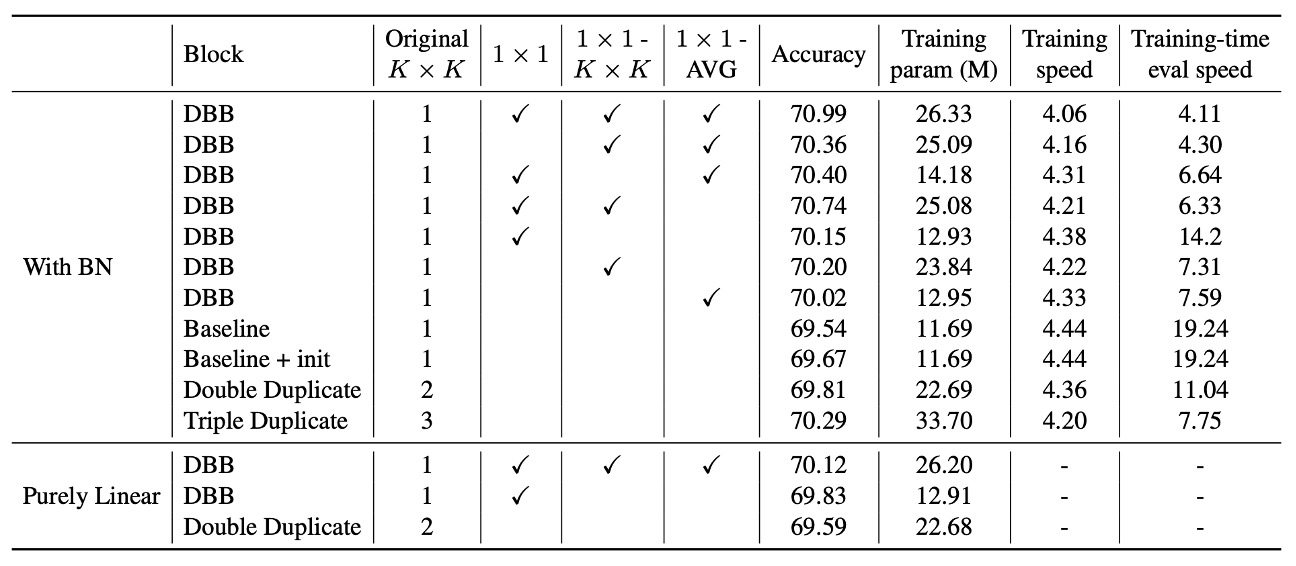

The authors conducted a series of ablation experiments based on ResNet-18 to validate the importance of diverse connections and non-linearity during training.

The results show that removing any branch of DBB leads to a decrease in performance, indicating that all branches are indispensable for improving performance. Additionally, even with only three branches, the accuracy exceeds 70%, demonstrating the effectiveness of diversified structures. In resource-constrained scenarios, using only 1×1 and 1×1−AVG branches can build a lightweight DBB, with only a slight decrease in accuracy but significantly better training efficiency.

Further comparison between DBB and duplicate blocks reveals that even when the total number of parameters is the same, DBB outperforms structures with duplicated convolutions. For instance, the accuracy of the (K×K + 1×1) combination (70.15%) is higher than double K×K (69.81%), showing that a weaker component combined with a stronger one is more advantageous than two equally strong components.

Similarly, DBB with (K×K + 1×1 + 1×1−AVG) (70.40%) outperformed triple K×K (70.29%), even though the latter's training parameters are 2.3 times larger, further proving that the diversity of connections is more important than merely increasing the number of parameters.

To confirm that these improvements were not solely due to different initializations, the authors created a "baseline + init" control group, initializing ResNet-18 with the full DBB-Net and training under the same settings. The final accuracy (69.67%) was comparable to the baseline with standard initialization, indicating that the performance improvement was not due to initialization strategies.

Finally, the authors also analyzed the impact of BN on the non-linearity during training.

When BN was moved to after the branch addition, making the block purely linear during training, the performance improvement was significantly reduced. For example, the accuracy of the (K×K + 1×1) DBB under this condition was only 69.83%, lower than the original DBB (70.15%). This shows that even without considering training non-linearity, diversified branches still improve model performance, but the non-linear structure with BN further enhances the learning capability.

The experiments also examined training and inference speeds, and the results showed that increasing the number of training parameters did not significantly affect the training speed.

Conclusion

This study presents a novel convolutional neural network building module: DBB (Diverse Branch Block), which enables the fusion of diversified branches through a single convolution.

The experiments demonstrate that DBB can effectively improve the performance of existing architectures without increasing inference costs. The key factors contributing to DBB's superiority over regular convolution layers are diversified connections and non-linearity during training. This research provides new directions for future network designs, showcasing a more flexible and efficient approach to convolution computation.