[15.05] U-Net

The Dawn of Integration

U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation

In the early days of VGG, there were still many unmet needs.

Researchers found that traditional CNN architectures couldn't provide the fine-grained details necessary to address the challenges of biomedical image segmentation.

Thus, this work was born, which has become a classic in the field of image segmentation.

Defining the Problem

In contrast to the image classification field, where everyone is content with ImageNet, biomedical image segmentation researchers were not as fortunate. In this field, the amount of available data for training is extremely limited, not enough to support the training requirements of deep learning.

The solution to this problem wasn't very clear. One approach was to slice the training data into multiple small pieces to generate more training samples. However, this resulted in another issue: the loss of contextual information, which in turn reduced segmentation accuracy.

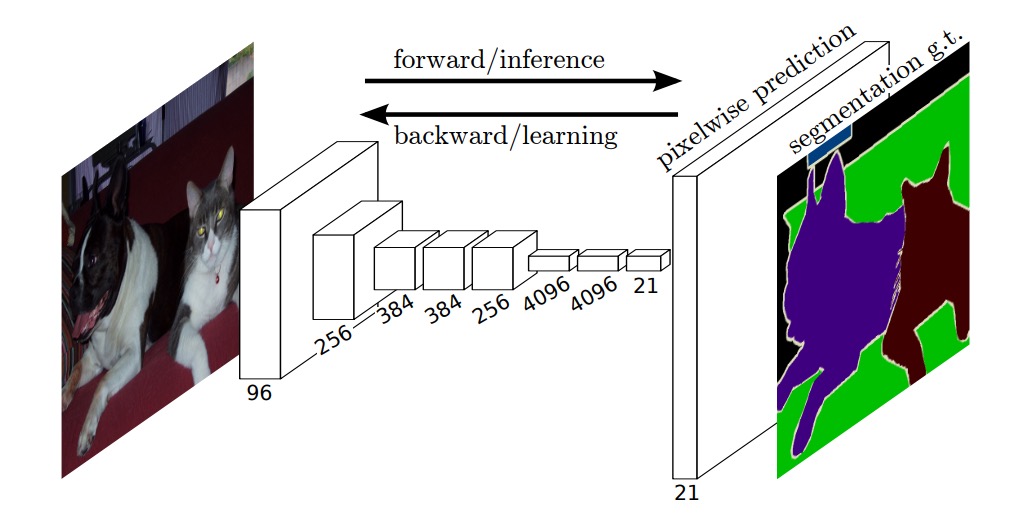

Around this time, another study proposed the fully convolutional network (FCN) architecture, which provided some inspiration to the authors.

Perhaps this architecture could be applied to biomedical image segmentation, solving the problem of losing contextual information.

Solving the Problem

Using the entire image indeed solved the problem of losing contextual information, but the issue of insufficient data remained.

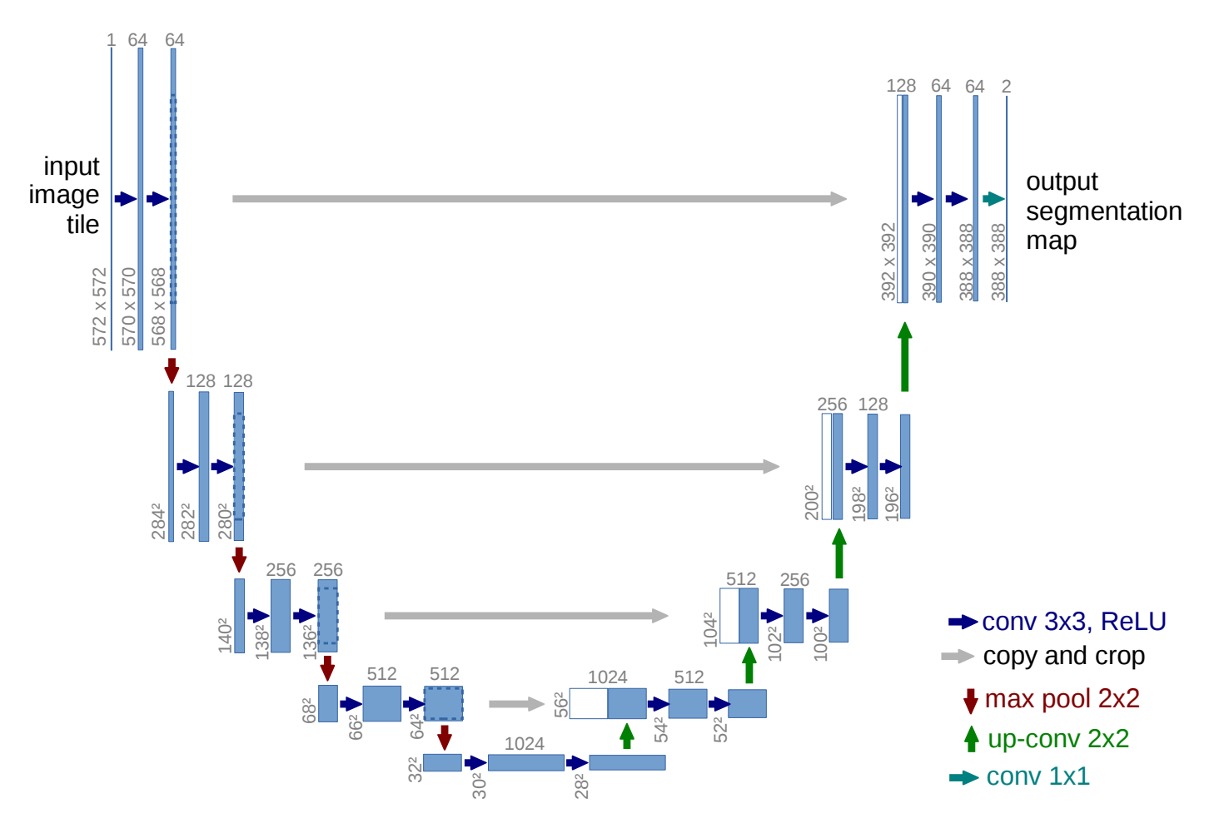

Thus, the authors proposed the U-Net architecture, as shown in the diagram below:

By reusing high-resolution feature maps, the accuracy of segmentation was improved while reducing the model's dependency on large amounts of data.

At this point, you can temporarily ignore the numbers, as the authors did not use padding in the convolutional layers. Hence, with each convolution layer, the size of the feature maps decreases. This might distract someone seeing the architecture for the first time, preventing them from appreciating the structure as a whole.

Let's cut the image in half and first look at the left side:

This is what we commonly refer to as the Backbone, which can be freely swapped for different architectures. If you like MobileNet, use MobileNet; if you prefer ResNet, use ResNet.

A basic Backbone design has five downsampling layers, corresponding to the five output layers in the image above.

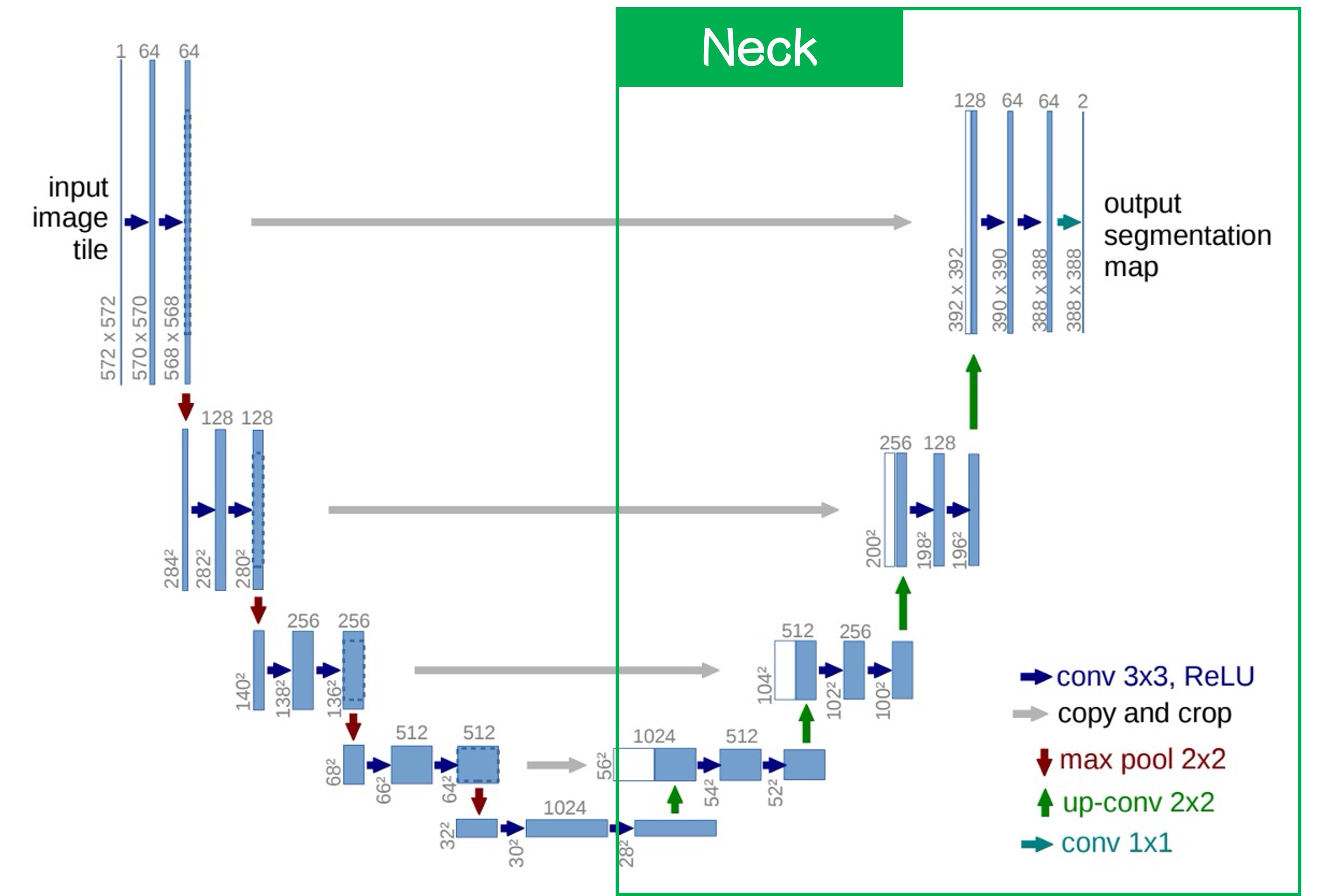

Next, let's look at the right side:

This is the Neck, characterized by upsampling from the lowest layer. The method can be simple interpolation or more complex deconvolution; in this paper, the authors used deconvolution.

After upsampling, we obtain higher-resolution feature maps, which are then fused with the feature map from the previous layer. The fusion method can either be concatenation or addition; the authors used concatenation in this paper.

After this process, we obtain a segmentation result with the same size as the original image. The number of channels in the output controls whether it’s a binary or multi-class segmentation. For binary segmentation, only one channel is needed; for multi-class segmentation, multiple channels are required.

If you opt for addition instead of concatenation, it leads to another classic architecture: FPN.

Another popular terminology would refer to the Backbone as the Encoder and the Neck as the Decoder.

This is because the task here is also an image-to-image transformation, conceptually similar to the AutoEncoder design.

Discussion

ISBI Cell Tracking Challenge 2015

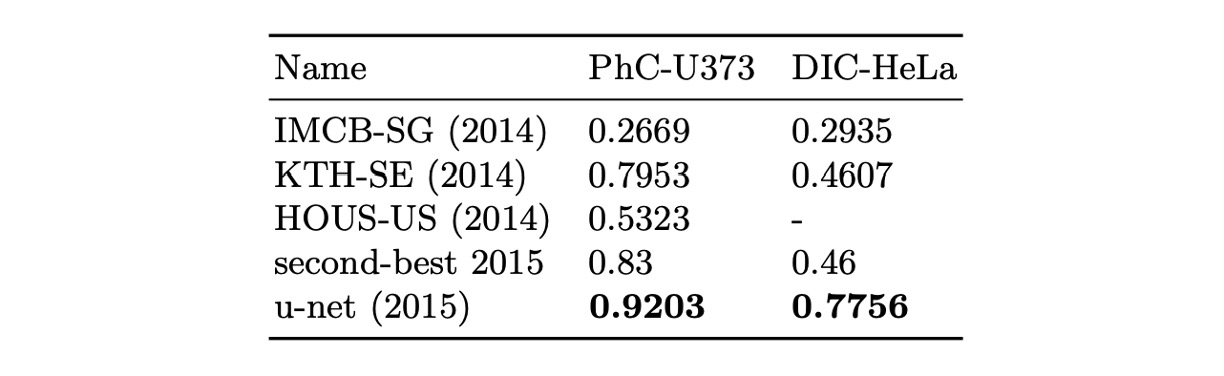

The authors applied U-Net to the ISBI 2014 and 2015 Cell Tracking Challenges:

- In the PhC-U373 dataset, it achieved 92% IOU, significantly surpassing the second place at 83%.

- In the DIC-HeLa dataset, it achieved 77.5% IOU, again greatly outperforming the second place at 46%.

These results demonstrate that U-Net performs exceptionally well in different types of microscopy image segmentation tasks and outperforms existing methods by a large margin.

Conclusion

The design of U-Net preserves high-resolution feature maps and integrates contextual information, improving segmentation accuracy while reducing data requirements. This architecture is simple, scalable, and applicable to various image segmentation tasks, including cell segmentation, organ segmentation, and lesion detection.

Compared to FPN, the concatenation structure results in a higher number of parameters and computational load, which can be a concern when there are restrictions on model size. Each architecture has its strengths, and it’s valuable to learn different designs and choose the one most suitable for the task at hand.